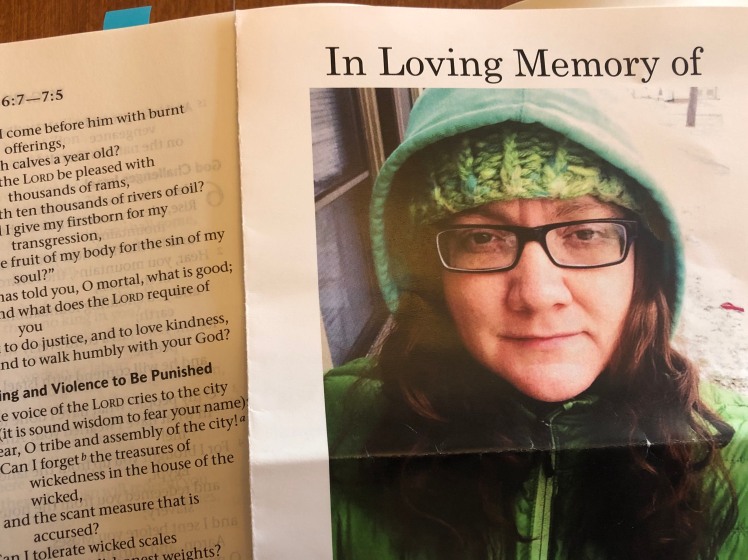

About thirty years ago, I got to know a fellow middle schooler named Kimberly Weaver. She was both smarter and funnier than me, and while we went to different schools, I was glad that church gave us twice-weekly opportunities to connect. But she went to college at Bethel, while I headed east. Coincidentally, I joined her alma mater’s faculty not long after Kim’s dad retired from it, the same year that Kim and her husband Nate moved to Bolivia to do community development work with the Mennonite Central Committee. A few years later, they returned to Minnesota, and I heard that Kim went back to school to become a nurse. Then our twins ended up on the same youth baseball team as Kim’s son, and we reconnected.

But we saw each other rarely enough that I didn’t realize until this August just how sick Kim was. Like her daughter, our kids participated in our school district’s summer orchestra camp, but we didn’t see Kim at the closing concert. That night, we read a Facebook message from one of her friends explaining how advanced the cancer was. A few weeks later,

she was dead.

“There’s something profoundly wrong with today,” said the pastor at this morning’s memorial service, “something profoundly backwards.” After all, a mother of two was dead at age 44. Worse yet, Kim had lost her battle with cancer just eleven years after her dad did. “This whole dying-decades-before-your-time thing is utter bullshit,” said Kim’s brother this morning. It’s not a message you often hear from Baptist pulpits, but he was exactly right.

“I wish I weren’t here,” the pastor admitted. But he continued, “And yet there’s nowhere else I would rather be.” Clearly, many people felt the same way. The old church was filled.

First, it gives us a chance not only to proclaim our belief in the Resurrection, but to practice resurrection.

That’s what I had called it in

a short “Meet the Faculty” video that Bethel happened to release earlier this week. “For a Christian,” I had said, “history is a way of

practicing resurrection… a way of saying that death does not have the final claim, that memories can endure, that people’s lives matter long after life has ended.”

As Nate (a historian himself) urged us at the close of his eulogy, we should “remember Kim’s stories; let them become your stories… If you do that, she will continue to be with us.” Truly, Kim came more and more to life for me as her husband, daughter, brother, and friends from high school, college, church, and work shared distinctive memories of the multi-faceted woman they knew.

Listening to those testimonials, I marveled at the grace that lets people find eloquence in exhaustion and turn pain to poignancy. Throughout the service, and in many private moments before and after, I saw people speaking and singing words of sorrow and anger and humor and lament and celebration and distraction and, above all, comfort.

But for once, I found myself at a loss for words. (“He’s never had an unpublished thought” is how one retired colleague introduced me to a friend.) Greeting Nate before the service, I mumbled platitudes and stumbled through questions that I hope were only inane, but probably closer to stupid.

And I’ve felt similarly awkward in my prayers concerning Kim and her family. God is never harder to approach than when the problem of evil comes to life in someone’s untimely death. The day before I

preach and teach for Reformation Sunday, attending this kind of funeral reminded me again of Martin Luther’s observation that God is sometimes a “

hidden God,” his purposes utterly beyond knowing.

So I felt more sympathetic than usual with

the frustrated questions that preceded our scripture reading for the service:

“With what shall I come before the Lord,

and bow myself before God on high?

Shall I come before him with burnt offerings,

with calves a year old?

Will the Lord be pleased with thousands of rams,

with ten thousands of rivers of oil?

Shall I give my firstborn for my transgression,

the fruit of my body for the sin of my soul?”

What do you require of us, God? What words will you hear? How should we live, knowing that our lives can be cut so short?

Here’s the prophet’s answer, the verse that the pastor read this morning:

He has told you, O mortal, what is good;

and what does the Lord require of you

but to do justice, and to love kindness,

and to walk humbly with your God? (Mic 6:8)

I don’t know if this is a good enough answer to the problem of Kim’s death, but remembering Kim’s life reminded us mortals to do justice, whether in rural Bolivia or urban America; to love kindness, as shown to everyone from her kids to her patients; and to walk humbly through it all.

We will find comfort, the pastor explained, “in taking up the unfinished work of her life.”

Peace be to Kim’s memory.